The Second Loop: Amsterdam, Museums, and Lost Agency

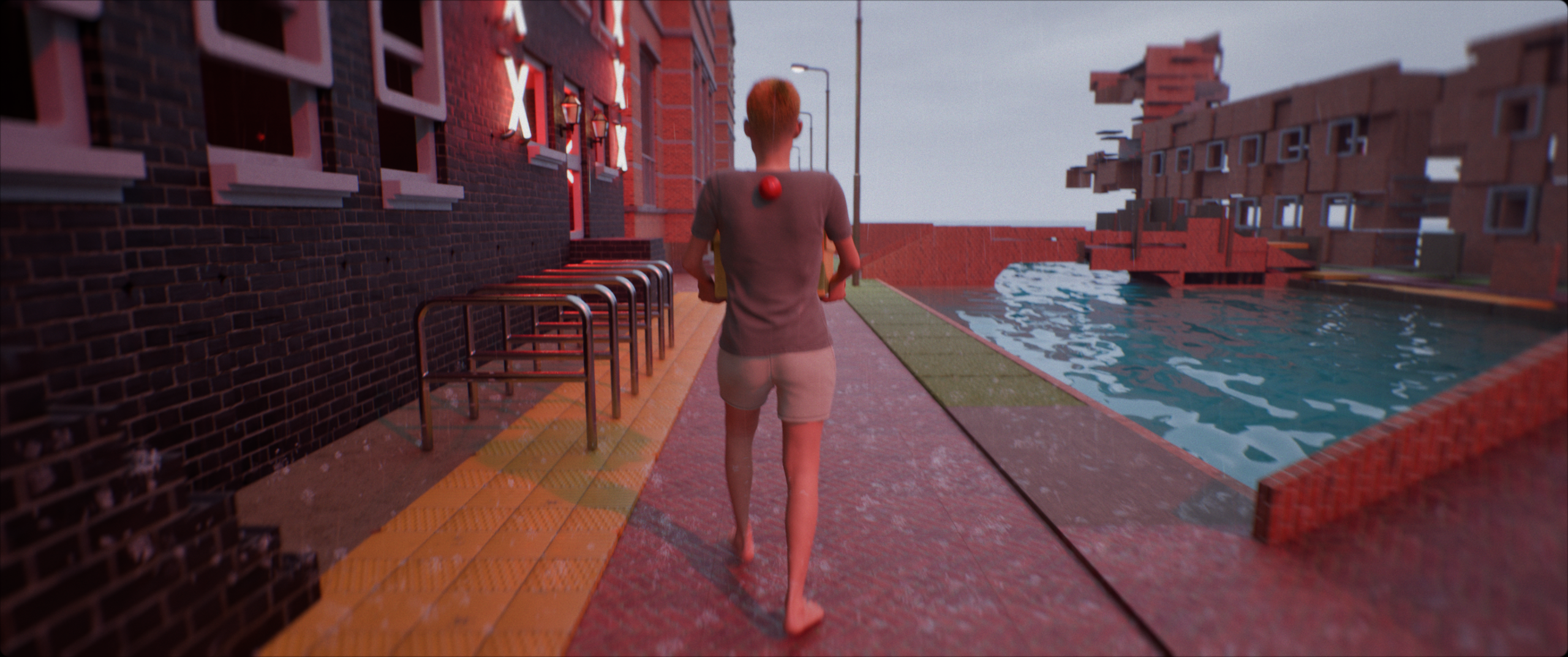

Alongside the Ziggurat loop, the film unfolds a second story loop set in a modular version of Amsterdam. This loop shifts ESHRAQ outward, into institutional space, urban architecture, and questions of agency.

Building a Modular Amsterdam

The second loop follows the soul of Liz Hoekstra, an assistant curator in a fictional museum.

The architecture of the city is heavily informed by my lived experience of Amsterdam. Having lived here since 2018, it has become my home. For this model, I created sampled materials based on the city’s most common architectural elements. Red brick walls, bike lane asphalt, grass modules, and more. For example the museum’s facade is a very simplified version of old Stedelijk Museum building.

In ESHRAQ, I called my version of the museum, STAD MUSEUM AMSTERDAM. In this first revision I used 11,574 modules. with 2 main floors and basement.

My initial idea was to build only a museum, but this gradually expanded into a city-scale model. Here are some detail shots from various zones of the city model:

The city developed a clear division between residential and commercial areas. The residential zones became chaotic, with modules placed irregularly. This began as an accident but slowly started to feel appropriate, reflecting the precarious housing situation in Amsterdam.

Inside the Museum

The idea of building a museum within ESHRAQ was sparked by a visit to the Stedelijk Museum in the early summer of 2025. During that visit, I encountered two works that stayed with me for very different reasons.

The first was Pamela Rosenkranz’s exhibition Liquid Body. I can be cynical at times, but this exhibition left me feeling unexpectedly empty. It reinforced a long-standing disillusionment I have with certain strands of contemporary art that rely heavily on production value and grand gestures while remaining conceptually thin.

To me, the work appeared to critique capitalism while fully participating in it. Highly produced, meticulously polished, and strangely void. As if capitalism itself required representation in order to be acknowledged. Perhaps this reading is too harsh, and the work undoubtedly operates within its own discourse, but regardless, the encounter became a useful provocation.

That provocation carried directly into ESHRAQ.

In the film, this encounter is reconfigured into a fictional museum scenario. One of the assistant curator’s tasks is to fill empty Amazon boxes with cash sourced from the museum’s basement. The institution appears to be feeding its own money back into the artwork in an attempt to sustain both its cultural legitimacy and its financial value.

Transparency as Performance

The second trigger was encountering Ahmet Öğüt’s Barricade in the collection. Next to the work were framed correspondences between the museum and the artist regarding a request to loan the piece to student protests in solidarity with Palestine. The museum politely rejected the request, citing contractual obligations. More context can be found in this article.

What struck me was not the refusal itself, but the way the refusal was framed. Presenting the correspondence as a gesture of transparency felt deeply odd. By exhibiting its own inaction, the institution appeared to retain an image of moral clarity.

Doing nothing became aestheticized.

At the same time, I am conscious of the historical moment we are in. Cultural institutions today are increasingly under pressure, operating within a landscape shaped by the rise of fascism, shrinking public imagination, and growing hostility toward the very idea of shared civic spaces. In such a climate, I hesitate to be unconditionally harsh. Killing the messenger carries its own consequences. A weakened or dismantled institution leaves no message at all.

Still, this tension remains difficult to ignore. Over the years of living in the Netherlands, I have repeatedly observed a pattern in which institutions maintain an ethical posture through procedural correctness, while avoiding direct action. Responsibility is deferred, risk is minimized, and transparency becomes a substitute for engagement.

I don’t mean to see the situation in simple terms. I have experienced many powerful exhibitions in this museum as well. Those moments are rightly celebrated. But moments of hesitation, complicity, or withdrawal often pass without the same level of attention.

Still Life and the Aesthetics of Inaction

In response, I introduced another layer in the film. A fictional exhibition titled Still Life, commissioned to a fictional Austrian artist, Clara Gruber Hoffman.

The work references Dutchbat and Dutch government’s complicity in the Serbian genocide. In the film, doing nothing becomes an aesthetic gesture.

This lack of agency becomes especially charged within ESHRAQ. The UN soldiers are shown wearing their helmets as Agent Cores. These orbs are agents that have lost their agency. 570 of them.

Closing

The Amsterdam loop extends ESHRAQ into institutional space, not to offer critique from a distance, but to simulate how agency is negotiated, deferred, and sometimes aestheticized from within. By placing these dynamics inside a simulation, the film does not judge them from above. It simply lets them run.

Together, the Ziggurat loop and the Amsterdam loop form the first structural layer of a much larger project. What I presented here is not a finished film, but a foundational section. Over the coming period in 2026, I plan to expand ESHRAQ into a feature-length cinematic work, adding several new story loops that unfold across different historical, political, and mythological terrains. Each loop will further test how simulation, narrative, and ontology reshape one another.

Alongside the film, I am also developing ESHRAQ as a growing installation format, with sculptural elements, spatial staging, and photographic works emerging from within the simulation itself. These outputs are not documentation, but parallel expressions of the same system.

If you are interested to keep in touch with future updates, please feel free to subscribe to the newsletter below: