Cinema, Simulation, and Ontology

It’s been a while since my last post here.

I spent some time recently redesigning this blog to make things more streamlined. With this new layout comes a more comprehensive report of what I have been working on during the second half of 2025.

During that period, I had the opportunity to show my work at Emerging Exits in Arnhem (1 October till 3 November). Curated by Jacco Ouwerkerk and Marijn Bril, the exhibition took place in the Diogenes Bunker, one of the largest bunkers built by the Germans during World War II. Responding to this context, I prepared a cinematic experience sourced entirely from ESHRAQ’s simulated environment. It felt like the right moment to turn ESHRAQ into a film stage.

I had been carrying a few ideas for a script for some time. They were slowly simmering in the background but never fully surfaced, until the twelve-day war happened in Iran. Following the horror unfolding back home from the relative safety of Amsterdam was deeply unsettling. At the same time, it forced something into focus. Within a week after the war ended, I managed to write the first draft of the film script.

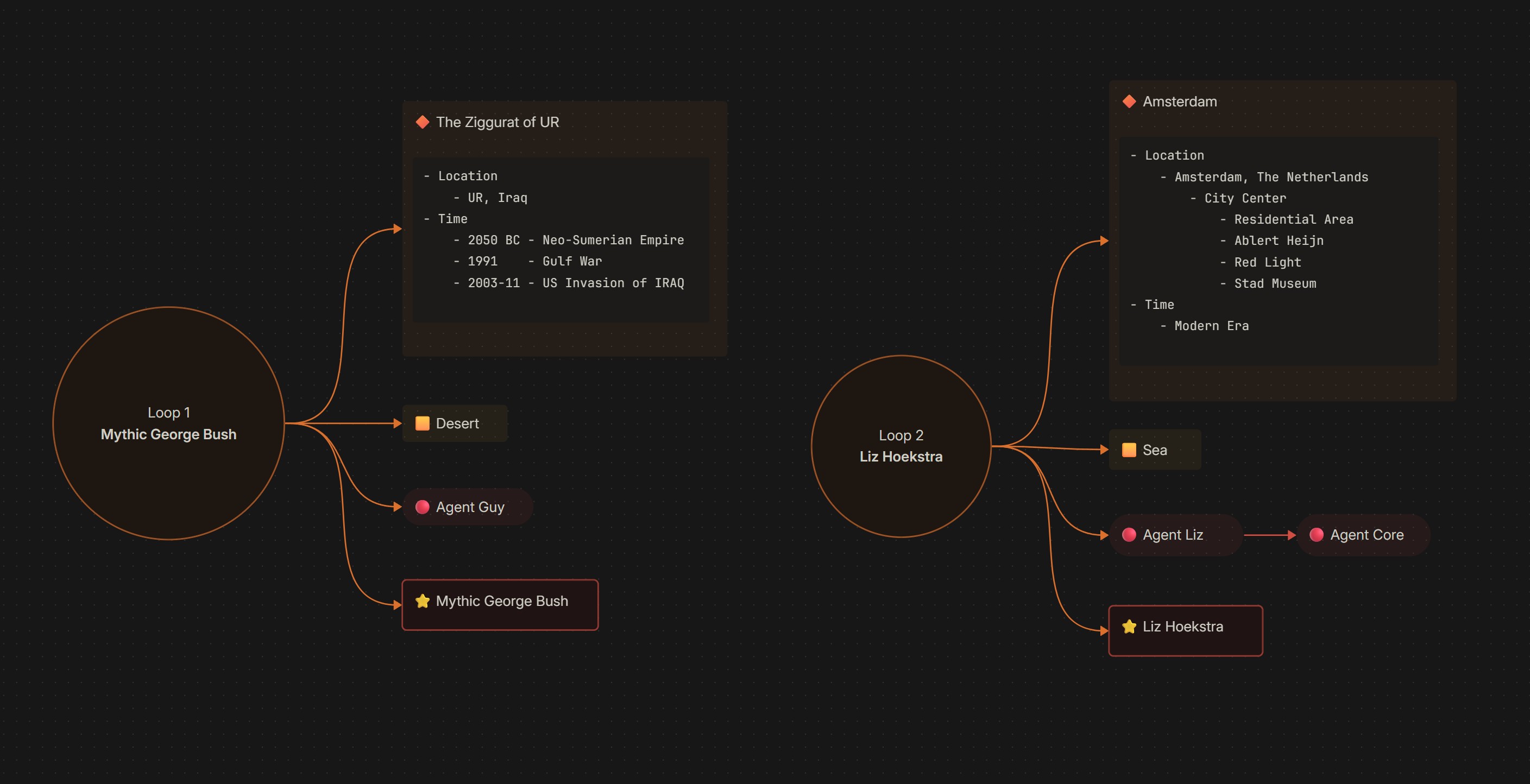

When I say film, I mean two story loops. Both are based on ESHRAQ, but they unfold in completely different models. One takes place in the Ziggurat of Ur, the other in a modular version of Amsterdam.

This post focuses on the first loop, and on what it meant to turn a simulation into cinema.

To get a sense of the film, you can watch and excerpt from the first 2 minutes of it here:

Why Cinema, Why Now

One of my main motivations for working cinematically with a simulation is that cinema remains a very potent medium for unraveling complex webs of knowledge and information in a tangible way.

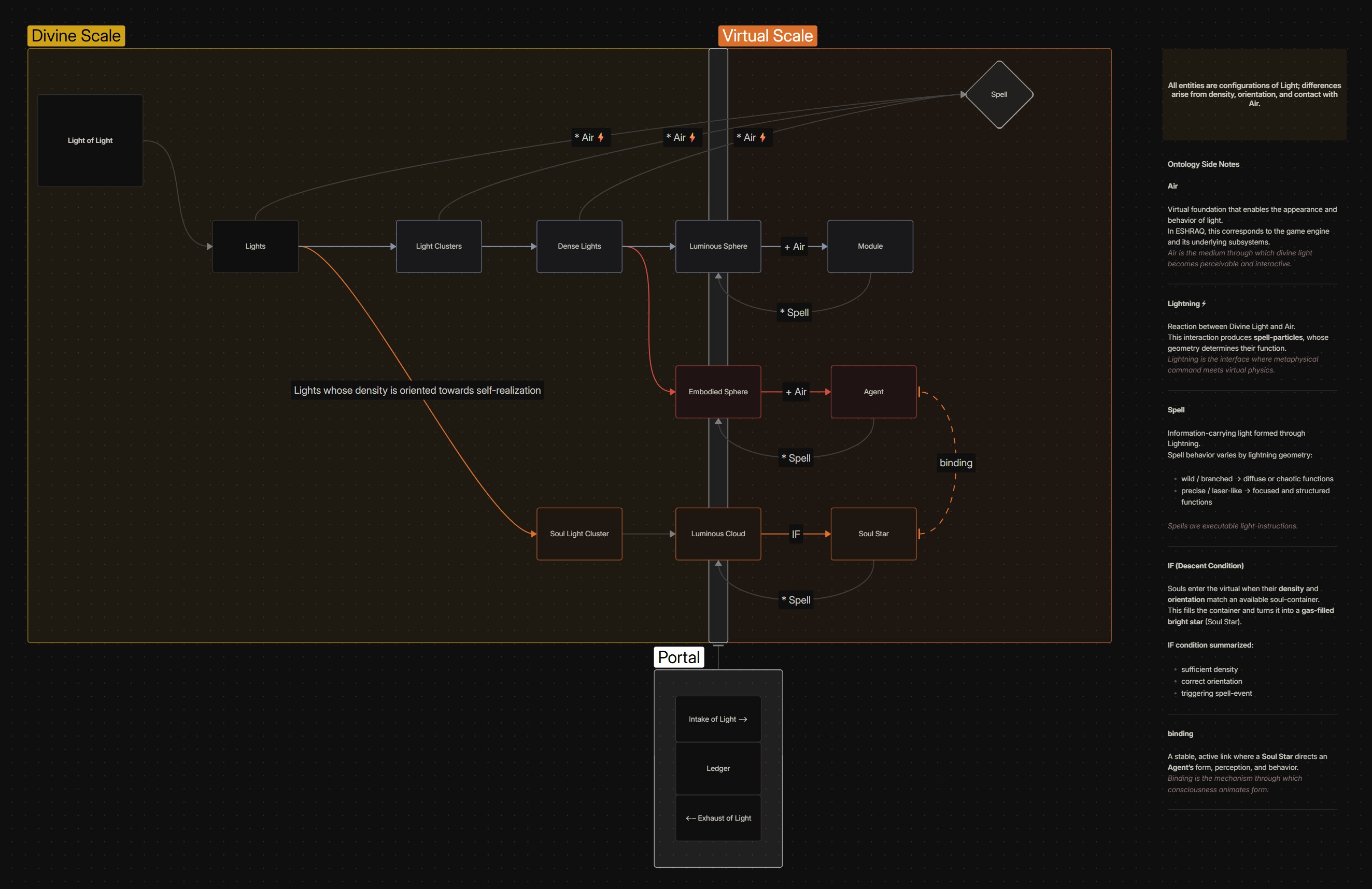

I can talk or write about ESHRAQ’s ontology for hours and still miss essential aspects of it. But within a twenty-minute film, this world and its internal logic begin to illuminate themselves. The ontology becomes visible through movement, rhythm, sound, scale, and duration. To me, this feels like a very efficient form of compression, one that cinematic language uniquely allows.

Throughout the film, this ontology of light becomes the ground on which new stories can exist. These stories unfold as loops. You can call them story loops if you will. They allow complex expressions to emerge from a relatively simple and grounded simulation.

Writing the Film With the Simulation

I wrote the initial draft of the film script in Scrivener, which I would recommend for scriptwriting and long-form writing in general. At that stage, the script captured a clear direction for the film, but it was never meant to dictate its final form.

Once I moved into production in Unreal Engine, the relationship between the script and the work began to shift. I had roughly two and a half months to turn the draft into a twenty-minute film, but rather than following the script rigidly, I treated it as a guiding force. Many decisions were made while recording scenes, blocking movement, and working directly with the simulation. Several moments in the final film deviate from the original script, emerging instead from the constraints, affordances, and unexpected behaviors of the system itself.

In practice, the writing process became both top-down and bottom-up. While navigating ESHRAQ as a simulation, I encountered moments that felt too strong to ignore. These moments were logged back into the script, allowing play, system behavior, and authorship to feed back into one another.

This approach kept me closely aligned with the internal logic of ESHRAQ and with the limits and potentials of Unreal Engine. The script provided orientation, but the simulation determined how ideas could materialize. In that sense, the film was shaped through a dialogue between intention and system behavior, rather than direct execution.

The modular structure of ESHRAQ played a crucial role in this process. The Ziggurat of Ur already existed as a modular system and only required specific modifications. The same applied to agents, environments, and architectural logic, allowing changes to propagate through the system without needing to be explicitly scripted at every level.

Working this way also transformed cinematography. Being able to inhabit the film stage freely and repeatedly allowed me to survey locations for camera movement and framing before committing to shots. Using Unreal’s Cine Camera Actor enabled movements that would be impossible or dangerous in real-world filming.

Here is an early test of a weighted camera-follow system, designed to simulate the physical mass of a real camera as it tracks the subject:

This way of working is not unique to ESHRAQ. During the pre-production of Dune: Part Two, Unreal Engine was used extensively for virtual scouting and shot planning in a simulated desert environment. Having access to a navigable film stage before shooting fundamentally changes how cinematic decisions are made.

You can read more about that process here.

I also chose to keep glitches and artifacts that emerged naturally. Collision errors and clipping are not mistakes to hide. They are part of the living conditions of a computational world.

Cinematic Language and Format

I chose a 2.55 wide aspect ratio, with a final output resolution of 4096 × 1716. This very wide format, combined with emulated Panavision C-Series anamorphic lenses, creates an immersive frame that wraps around the viewer’s vision.

In post-production, I leaned into virtual production techniques such as lens distortion, film grain, color work, flares, and bloom, aiming to get as close as possible to the texture of real cinema lenses.

The post-production was handled in two passes. The first took place inside Unreal Engine, where I captured the raw camera image. The second pass was done in DaVinci Resolve, where I introduced lens distortion, color work, and film grain to push the image closer to a cinematic texture.

This choice was also influenced by how much I admired the image quality of Star Wars: Andor, as well as Dune: Part One. There is something about that visual language that holds science fiction and gravity at the same time.

When Cinema Rewrites Ontology

Something unexpected happened while writing cinematically. Ideas emerged that had never appeared during the simulation phase. Switching into a storytelling mindset changed how the world itself wanted to express things.

In that sense, the film did not simply visualize ESHRAQ. It actively generated new ontological ground for it. Narrative pressure, pacing, framing, and duration reshaped how the simulation behaved and what it could express. Expanding the film will continue to influence how ESHRAQ’s ontology evolves.

The Opening: Birds, Annihilation, Becoming

The first eight minutes of the film function as an introduction to ESHRAQ’s illuminationist foundation.

Thirty birds appear on screen, all constructed from modules. Each has the head of a Huma bird, but in different states of decay. They initially exist in a divine realm, receive a calling, and are then deployed into the desert of ESHRAQ.

For Iranian viewers, this references The Conference of the Birds by Attar. In that poem, a group of birds sets out on a journey to find truth, only to realize that they themselves are what they were searching for.

In Sufi terminology, this journey involves fanā’, the annihilation of the self, followed by baqā’, remaining or becoming.

In the film, I invert this logic. The thirty birds begin as a whole and are then fragmented and dispersed back into the desert. This individuation is justified by history. We know where they came from.

In ESHRAQ, all thirty birds are in fact one bird, the Huma, encountered across different temporalities. Unlike Attar’s birds, which come from different species, these are the same mythic entity fractured across time. The plurality does not come from identity, but from accumulated meaning and historical interpretation.

Light, Bombs, Modules

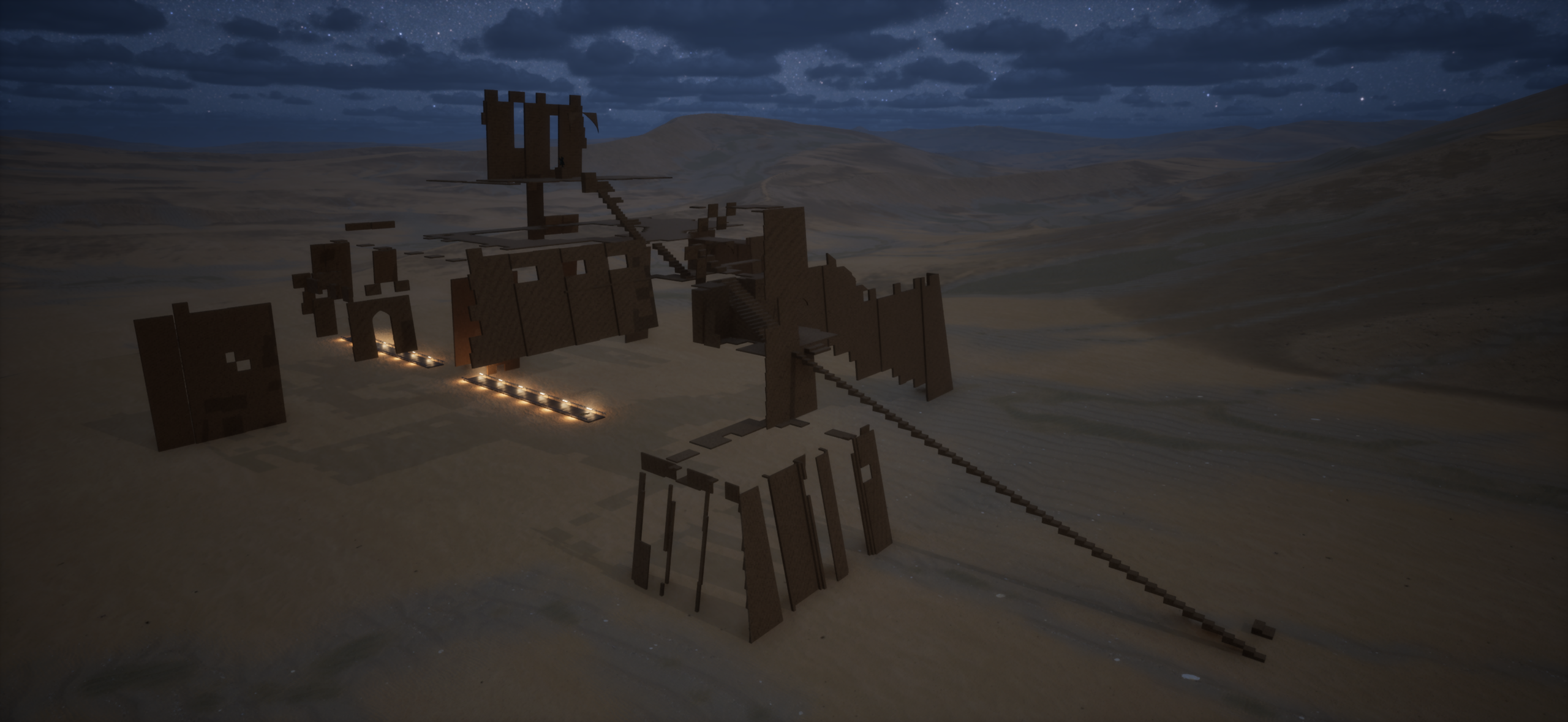

The birds pass through a very bright rectangular window of light and enter the desert. They drop rocket-like bombs that open mid-air before touching the ground. Each bomb releases an orb of light, which falls, densifies, and gradually turns into an architectural module such as a wall, stair, or floor. The empty shell then returns to the sky.

This repeats in time-lapse until the entire Ziggurat is constructed in a dense cascade of light.

At first, making the scene shown above felt complex. Once I realized that all Ziggurat elements inherit the same base module class, the problem collapsed into a systems question. I implemented a shared light-VFX logic to drive the modules sequentially, then ran the simulation in Unreal. With slight randomization in the spawn timing, the engine resolved the composition on its own, allowing the scene to emerge within a few hours.

In this context, making the film was not merely a matter of animation. It required writing procedural logic that could unfold over time. When a procedural system behaves as intended, it introduces a different kind of satisfaction, by letting the system carry part of the authorship.

This opening sequence establishes the internal logic of the world so that everything that follows can operate through it.

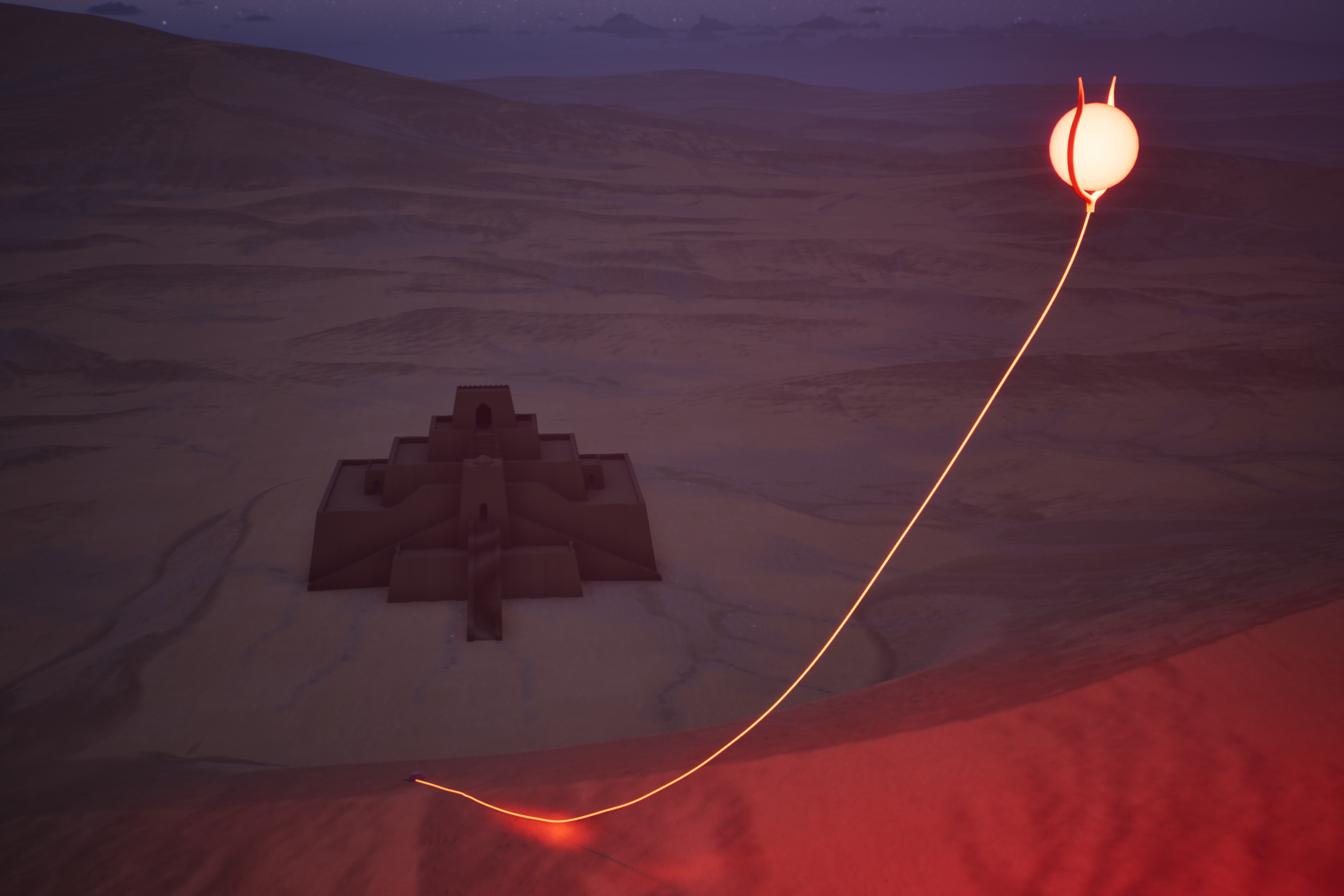

Souls and the Ziggurat Loop

Within the film, the Ziggurat becomes a deep object where the first story loop unfolds. The soul of Mythic George Bush is spawned into the site.

I spent a long time thinking about the design of souls in ESHRAQ and how they could be materialized. I eventually arrived at the idea of representing them as luminous red-orange spheres, almost like miniature stars hovering above specific sites.

Each soul connects through a bright thread to an idle agent on the ground. When the soul becomes active, it forms a bond with the agent. In the film, the camera follows this connection as Mythic George Bush begins to speak about unfinished business.

Mythic George Bush, or MGB, is an amalgamation of George Bush and his father. I wanted to test the boundaries of what a soul could be. Can it be composite? Can it be an infusion of multiple figures? What other chemistries might be possible?

Through MGB, the history of the Ziggurat is retold from multiple vantage points. Ancient cosmology sits next to the Gulf War and the US invasion of Iraq. This section was sparked by a photograph of American soldiers ascending the Ziggurat. The contradictions in that image became a driving force behind this loop.

Soul View and the Imaginal

Another important design element is what I call the Soul View, developed together with Graphic Designer Danial Alemasoum. We wanted a visual language rooted in ESHRAQ’s modular logic while drawing from Iranian visual culture.

We were inspired by glass and mirror architecture, especially the Shrine of Imam Reza in Mashhad. I was born in Mashhad and we lived there until the age of 9. As a child, I used to stare at mirrored ceilings and try to find myself within the reflections. The architecture never allowed it.

This experience shaped the Soul View. It produces fragile, mirage-like images that appear and disappear. It reveals information about souls that cannot be materialized on the ground.

There is also a reference to sand as the source of glass. The film begins in a desert, which I see as a strong metaphor for the imaginal world. A place where things dissolve, but also where sand and light conspire to form endless images.

Physical Dimension

For Emerging Exits, I introduced a physical element sourced from ESHRAQ. I created a lightbox containing the thirty Huma heads, aligned as if passing through the threshold of light again, but without wings.

Encountered without mediation, these objects invite interpretation. After watching the film, they acquire new meaning. The tension between these readings is something I want to preserve.

Behind the Scenes

The final element I added to the installation at the Diogenes Bunker was a behind-the-scenes video loop, displayed directly behind the main film screen. The screen was therefore two-sided. While the front presented the cinematic work, the reverse side exposed the conditions of its production.

This was a deliberate gesture. I wanted to make visible the fact that everything seen in the film is sourced from a simulation, and to acknowledge the systems, assets, and processes that made it possible.

The behind-the-scenes video was composed of five tiled views, each revealing a different layer of the work:

-

Conveyor-belt view

A long tile showing all the modules used in the film moving past in sequence, from the Huma bird heads to walls, floors, stairs, and other architectural elements. -

Material palette view

A tile presenting the full material library of the project, including mud brick, asphalt, concrete, water, stucco, and other surface systems used across environments. -

Agent view

A tile displaying all agents placed on a rotating platform in a T-pose, similar to a character selection interface. This emphasizes their status as potential actors within the simulation rather than fixed characters. -

Simulation playthrough view

A tile showing selected moments from live playthroughs inside ESHRAQ, highlighting how scenes emerged through interaction rather than pre-scripted animation. -

Spatial replica view

A larger tile depicting a replica of the bunker itself, modeled exactly as the installation was presented. This functions as a limbo space connecting the physical exhibition site to its virtual counterpart. I have written more about the concept of limbo spaces in an earlier post.

Closing

Showing this twenty-minute section of ESHRAQ confirmed something important for me. Cinema is not a secondary output of the simulation. It is a generative force that reshapes its meaning and even ontology.

Next post: the second story loop, set in a modular Amsterdam.